With two of the currently most hyped films in theaters having been viewed by me in a short timeframe, I thought it best, due to their natures, for me to link them in one post on this blog: as a single review of popular filmmaking now.

With two of the currently most hyped films in theaters having been viewed by me in a short timeframe, I thought it best, due to their natures, for me to link them in one post on this blog: as a single review of popular filmmaking now.

21 November 2009

Reviews: 2012 and Precious: Based on the Novel "Push" by Sapphire

Official Site: A Single Man

Though not yet officially linked by The Weinstein Company's official site, Tom Ford's upcoming film's (A Single Man's) own official site is apparently up and running, featuring not only a beautiful sample of the film's official score (composed by Abel Korzeniowksi) but also a link by which one, if interested, may read an excerpt from the book from which the film's official screenplay was adapted: Christopher Isherwood's A Single Man (1964).

Exhibition: Tim Burton at MOMA

13 November 2009

Announcement: The February Criterion Releases!

Criterion has always sought to bring you the best in classic and contemporary films, and there couldn’t be a better example of that than this February, when two long-requested masterpieces—Ophuls’sLola Montès and McCarey’s Make Way for Tomorrow—join the collection, along with two of the greatest films of recent years: Götz Spielmann’s Oscar-nominated Revanche and Steve McQueen’s Cannes-award-winning Hunger. All this, plus a George Bernard Shaw Eclipse set and Howards End on Criterion DVD!

07 November 2009

Trailer: A Single Man

O, my Film: According to Awards Daily, the official trailer for Tom Ford's upcoming filmic début A Single Man, adapted from the novel of the same title by Christopher Isherwood, has just been released via YouTube and it (embedded above), though not a significant departure from the earlier teaser version, is just spellbinding. I hope(!), my awe may not expire with the release of the full feature (scheduled for 11 December 2009).

02 November 2009

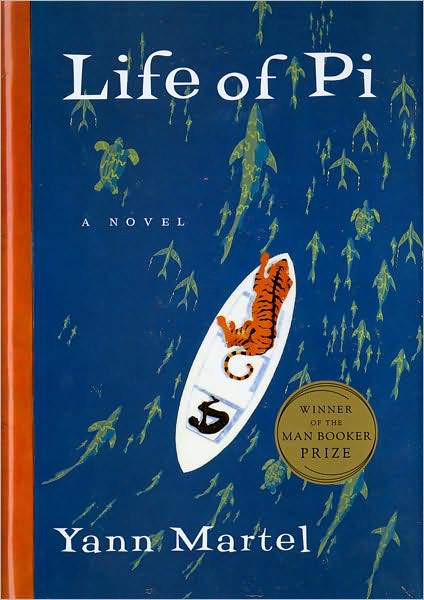

Preview: Life of Pi

Review: Where the Wild Things Are

Genre: Fairy Tale / Action-Adventure

Genre: Fairy Tale / Action-Adventure

Review: Antichrist

I've taken some time, since I've seen the film, to fully digest Antichrist - or, if not fully, then at least better than may have some other reviewers who were quick with the instinctual exclamations but lacking of the intellectual fervor that this film, as all others, deserves. Mr. von Trier has clearly tried to take his film-making to a very personal place with this obviously purgative venture into ethereal imagery and caustic relationships. The protagonistic couple, played admirably for their endurance by Willem Dafoe and Charlotte Gainsbourg, rub up against one another and also against their inhabited world with increasing friction that eventually surpasses the stimulating and transgresses into the chagrinning, irritating, and ultimately burning acts of animate bodies in conflict. Against one another they rub and fight and contrive scenarios that, to the non-endemic eye, read like hallucinated vorteces of sadomasochistic indulgence and occultural pain but, to the endemic, feel like natural off-shoots of deep emotional seeds, as if thick and woody flowers were grown out, from within, and shaped in so doing by the pressurized nature of their containers. While such story-telling and investigation are of course powerful and indeed shocking at times, the ending effect is one that does include beauty before it leaps into arcane over-indulgence and morbid inevitabilities. Mr. Anthony Dod Mantle's refulgent cinematography, albeit hyper-stylized, rescues itself from the edge many times and in the end constructs a visual field that, though rapt and sometimes wreckless, finds sense in the hectic screenplay. By frequently literally slowing the action down to near clinical observations of scenes in progress - especially the film's prologue and epilogue - he trains his camera to slice and cleave an inlet for its viewers through which they may see, feel, and access the tightly wound, balled, and precarious knots of fervor and intimacy upon which the entirety of the action rests; and, though meagre, such an inlet is just enough for me to commend him for the achievement by listing him at right with those Under Consideration for the best of the year in their respective film-making categories. I include there also Ms. Gainsbourg and Mr. Dafoe, who though not especially strong nevertheless admirably somehow resist complete over-indulgence and wrecklessness in their performances as well, firming up the heart of the piece that, though anomalously conformed, beats still. However, I do not include any other creator of the film, including Mr. von Trier himself, whose work though intriguing here I think leaves too much heart - and not quite enough head - on the table.

I've taken some time, since I've seen the film, to fully digest Antichrist - or, if not fully, then at least better than may have some other reviewers who were quick with the instinctual exclamations but lacking of the intellectual fervor that this film, as all others, deserves. Mr. von Trier has clearly tried to take his film-making to a very personal place with this obviously purgative venture into ethereal imagery and caustic relationships. The protagonistic couple, played admirably for their endurance by Willem Dafoe and Charlotte Gainsbourg, rub up against one another and also against their inhabited world with increasing friction that eventually surpasses the stimulating and transgresses into the chagrinning, irritating, and ultimately burning acts of animate bodies in conflict. Against one another they rub and fight and contrive scenarios that, to the non-endemic eye, read like hallucinated vorteces of sadomasochistic indulgence and occultural pain but, to the endemic, feel like natural off-shoots of deep emotional seeds, as if thick and woody flowers were grown out, from within, and shaped in so doing by the pressurized nature of their containers. While such story-telling and investigation are of course powerful and indeed shocking at times, the ending effect is one that does include beauty before it leaps into arcane over-indulgence and morbid inevitabilities. Mr. Anthony Dod Mantle's refulgent cinematography, albeit hyper-stylized, rescues itself from the edge many times and in the end constructs a visual field that, though rapt and sometimes wreckless, finds sense in the hectic screenplay. By frequently literally slowing the action down to near clinical observations of scenes in progress - especially the film's prologue and epilogue - he trains his camera to slice and cleave an inlet for its viewers through which they may see, feel, and access the tightly wound, balled, and precarious knots of fervor and intimacy upon which the entirety of the action rests; and, though meagre, such an inlet is just enough for me to commend him for the achievement by listing him at right with those Under Consideration for the best of the year in their respective film-making categories. I include there also Ms. Gainsbourg and Mr. Dafoe, who though not especially strong nevertheless admirably somehow resist complete over-indulgence and wrecklessness in their performances as well, firming up the heart of the piece that, though anomalously conformed, beats still. However, I do not include any other creator of the film, including Mr. von Trier himself, whose work though intriguing here I think leaves too much heart - and not quite enough head - on the table.

Grade: B: Saved by its tempering hands, this film risks tipping itself out of its whirl with too daring a proclivity to do so for me to call it any more or any less.